What feature makes the River Thames one of a small band of urban rivers? The fact that it is tidal, with the inflow and outflow of vast quantities of water twice a day leaving impacts as profound as the change that beachgoers are familiar with at Brighton or Scarborough. But not every Londoner knows this: a very knowledgeable friend of mine who was partly brought up in the city recently admitted they had no idea it was tidal.

Twice a day the moon’s gravity pulls litres of water away from, and back towards the sea, creating a seven metre change in the height of the water. This leaves the river appearing like a swollen channel at high tide or a very modest trickle sandwiched between two pebbly and discoloured beaches at its low point. But the tidal nature of the Thames is not just a geological quirk, but a fundamental aspect that shapes London's ecology, history, and urban experience,

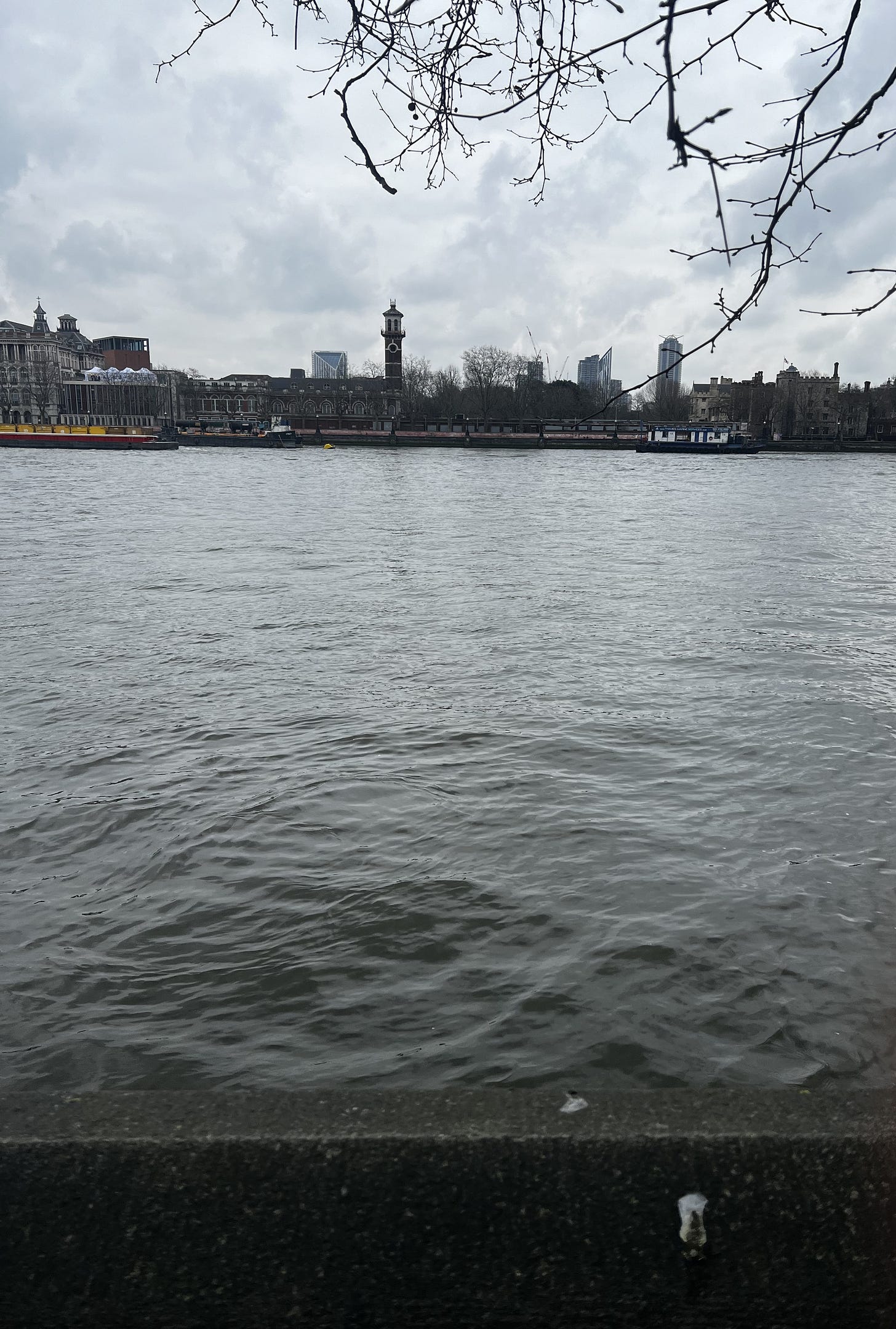

The Thames near Westminister; the same spot six hours apart

This seven metre change in the sea level makes the river an ever-changing vista for residents and travellers alike. The river acts as a collector, accumulating all sorts of items that end up in its waters — from everyday trash to offerings and precious lost items. This has transformed it into a valuable location for archaeological discoveries. The changing tides continuously expose new findings, and licensed mudlarkers explore the riverbed to discover these historical artifacts.

The banks of London's rivers have yielded diverse archaeological treasures, from Bronze Age weaponry to delicate Roman jewellery made of glass. The area has also revealed numerous ancient human remains — more than 250 skeletons have been discovered, among them a particularly remarkable find: a Neolithic skull dating back over 5,500 years.

The tide is high

But the tidal Thames can be a threat as well an opportunity. The inflow of water can create a risk of flooding given that the risk that a combination of a high tide and strong winds can lead to a dangerous inflow. That is what happened in 1953, when a severe flood along the east coast of England and Thames Estuary resulted in 307 deaths and £50 million (just over £1 billion in today’s money) worth of damage. Some 32,000 people were evacuated, and 160,000 acres of land was inundated with sea water and unusable for many years.

To counter the threat, the Thames Barrier opened in November 1982 and, along with eight other barriers and over 400 minor structures, has been the primary defence against the risk of flooding in central London. It spans 520 metres across the Thames near Woolwich and is made up of 10 steel gates that sit on the riverbed, and which can be raised in the case of a flood warning.

The Thames Barrier: an engineering marvel and lifesaver

It is a constant reminder of the threat that hangs over the city. As of April 2014, the Environment Agency has closed the Thames Barrier 221 times since it became operational. This because London is prone to flooding over the long term: the tides in London are rising 60 cm every 100 years. This is happening for a number of reasons: the south-eastern corner of the British Isles is slowly tilting, and sea levels are rising; London is settling into its clay bed; and global warming has also caused thermal expansion, so the volume of water has consequently increased.

Power source?

Looking ahead, this huge flow water should, in theory, offer the promise of a supply of renewable energy. According to the Port of London Authority, the Thames could provide local tidal energy opportunities. However, it is unlikely to come via traditional turbine technology because the space available on the river for construction of the infrastructure has become more constrained. Major development would also risk environment impacts for migratory species and protected habitats. So perhaps not.

There is one small scheme already in play outside the PLA’s arena. Two turbines beside Caversham Weir in Reading, Berkshire have harnessed the power of the river to generate electricity. Reading Hydro is forecast to generate about 320 megawatt hours (MWh) every year, equivalent to the annual electricity usage of just 90 average homes. Most of the electricity is purchased by Thames Lido, an open-air swimming pool located on the other side of the river. So, small but perhaps a stepping stone for other schemes.

Of course, the Thames is not unique, either globally or within its own national context. Tokyo, New York, Mumbai, Shanghai, and Buenos Aires all host rivers with tidal reaches. The last two are port cities and the tide is key for their maritime operations but New York’s Hudson River, Mumbai’s Mithi and Shanghai’s Huangpu rivers have similar pull to the Thames. In the UK Bristol, Newcastle and Liverpool all have tidal rivers but their urban reach is less than the Thames’s 150 km.

Its tidal movements are a reminder that the Thames is a living, breathing urban ecosystem. All rivers have a gently flow from their source to a sea or lake, but the Thames’s tidal nature makes it more of a dynamic feature than a simple static geographical feature. It is also a reminder that the river needs respect. It creates a diverse ecosystem home to fish, birds and even mammals like seals, but also brings with it dangerous currents and the ever-present threat of flooding.